Illustrative Image: Starlink Satellites Threaten South Africa’s SKA Telescope: Astronomers Warn of Interference with Cosmic Discoveries

Image Source & Credit: Spaceinafrica

Ownership and Usage Policy

As Elon Musk’s Starlink prepares for a full rollout in South Africa, astronomers are voicing urgent concerns about the potential disruption its low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellation may pose to one of the world’s most ambitious scientific projects—the Square Kilometre Array (SKA-Mid) in the Northern Cape.

The SKA, a multinational radio astronomy effort co-hosted by South Africa and Australia, is designed to be the most sensitive radio telescope ever built, probing the cosmos in frequencies between 350 MHz and 15.4 GHz. This band is essential for detecting faint, ancient radio emissions from galaxies, black holes, and the very origins of the universe. Yet, it overlaps with the downlink frequencies used by satellite internet providers like Starlink, raising fears that even weak radio “spillover” could swamp the delicate cosmic whispers that the SKA is built to capture.

“Imagine trying to study fireflies while someone shines a spotlight in your eyes,” explained Federico Di Vruno, co-chair of the International Astronomical Union’s Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky. “The faint cosmic signals are drowned out by artificial transmissions.”

A Fragile Quiet Zone Under Pressure

South Africa designated a “radio quiet zone” in the Karoo decades ago to shield its telescopes from terrestrial interference such as mobile phones, television broadcasts, and Wi-Fi. However, the regulations did not anticipate the rise of thousands of satellites orbiting above the horizon. Unlike terrestrial noise, which can be legislated locally, satellite interference is global—a problem that no single country can solve alone.

Adrian Tiplady, strategy and partnerships director at SARAO, stresses that while South Africa’s existing framework protects against ground-based interference, “new protections are needed for the skies.” Current discussions with regulators, including ICASA, involve embedding astronomy-specific safeguards into satellite licenses. These could include requirements for Starlink to steer its satellite beams away from telescope receivers or temporarily switch off transmissions during critical observations.

The Political Layer: Science Meets Policy

The debate is further complicated by SpaceX’s objections to South Africa’s Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) laws, which require foreign companies to align with local transformation and equity goals. While the government has indicated some flexibility in reviewing ICT regulations, it has reaffirmed its three-decade-long commitment to transformation policies. This creates a delicate balancing act: enabling technological innovation and economic inclusion while safeguarding South Africa’s role as a global hub for astronomy.

South Africa’s Astronomical Edge

From its unique southern-hemisphere vantage point, South Africa offers unparalleled views of the Milky Way’s galactic centre, making it a strategic site for astronomy. Recent discoveries showcase this advantage:

-

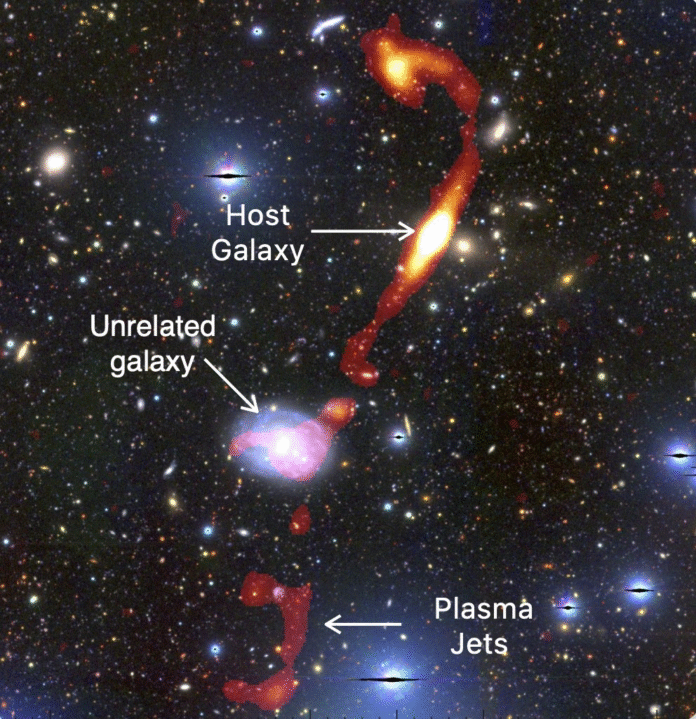

MeerKAT teamed with the European VLBI Network (EVN) to image a jet of plasma erupting from the supermassive black hole J0123+3044, a finding that sheds light on how black holes shape galactic environments.

-

The telescope has uncovered a radio galaxy 32 times the size of the Milky Way, alongside dozens of previously unseen galaxies.

-

The discovery of the colossal radio galaxy “Inkathazo” underscores how South African observatories are rewriting our understanding of the universe’s largest structures.

Mitigation Strategies on the Table

To protect this scientific treasure trove, astronomers are advancing several solutions:

-

Beam Steering or Transmission Pauses

Starlink satellites could be programmed to avoid transmitting when passing directly over sensitive SKA antennas. -

Spectrum Coordination Agreements

Regulators like ICASA could include legally binding astronomy protections in satellite operating licenses. -

Global Scientific Cooperation

Because satellites orbit across borders, the SKA Observatory is pushing for similar agreements with other mega-constellation operators, including Amazon’s Project Kuiper and OneWeb.

The Bigger Picture: Astronomy vs. the Satellite Era

In February 2025, South Africa reaffirmed its concerns at the 62nd session of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNOOSA), highlighting the “Dark and Quiet Skies” agenda. Itumeleng Makoloi, Director of Space Systems at the Department of Science and Innovation, explained that LEO satellites differ from geostationary satellites in their impact:

-

LEO satellites move quickly across the sky, causing their reflected light and radio emissions to smear over telescope images. This means they are less individually disruptive but more frequent.

-

Geostationary satellites remain fixed, producing constant interference in the same region of the sky.

-

The sheer density of LEO satellites, however, increases the probability of interference during long-exposure astronomical observations, where even tiny interruptions can ruin data.

Thus, the challenge is not just about satellite brightness or power, but about numbers, orbital height, and density of constellations. The world faces a delicate balancing act: enabling global internet access while ensuring humanity can still peer into the cosmos without artificial noise.

Conclusion

South Africa’s telescopes—MeerKAT, SALT, and soon SKA-Mid—are at the frontier of humanity’s attempt to answer cosmic questions: How do galaxies evolve? What is the nature of black holes? Where did the universe begin? But these efforts now face a new kind of interference—not from Earth, but from orbit.

As satellites multiply in the race for global broadband, South Africa’s astronomers insist on one point: preserving the dark and quiet skies is not only about protecting science, but about protecting humanity’s shared cosmic heritage.

The African Research (AR) Index is a comprehensive scholarly directory and database focused explicitly on journal publishers that publish and disseminate African research.

The African Research (AR) Index is a comprehensive scholarly directory and database focused explicitly on journal publishers that publish and disseminate African research.